The True Sun. Life on Earth is governed by the movement of the True Sun; that is the sun we see in the sky and not by the theoretical Mean Sun. The units of time in everyday use are defined in terms of the True Sun and are known as Apparent Solar Time.

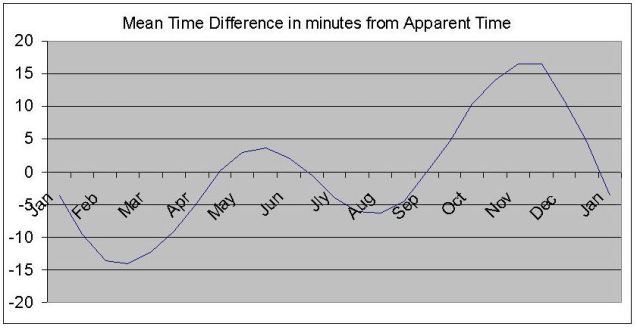

The Sun as a Time-Keeper. Because the Earth’s orbital motion is not uniform, there are corresponding variations in the apparent speed of the Sun along the ecliptic. For this reason, the hour angle of the True Sun does not increase at a uniform rate and therefore does not give an accurate measurement of time. To overcome this problem without losing the connection with the True Sun, the Mean Sun (as defined below) is used.

The Mean Sun is an imaginary body which is assumed to move in the celestial equator at a uniform speed round the Earth and to complete one revolution in the time taken by the True Sun to complete one revolution of the ecliptic.

The Mean Solar Day is the time taken for the Mean Sun to make one complete circuit of the Earth. In other words, it is the time taken for the Mean Sun to transit all 360 meridians of longitude. The time system based on the Mean Solar Day is known as Mean Solar Time.

Apparent Noon is when the True Sun is on an observer’s meridian of longitude. It is when the Sun reaches its greatest altitude above the observer’s horizon. In other words it is when the Sun is at its zenith.

Mean Noon occurs when the meridian of the Mean Sun coincides with the meridian of a place.

Local Mean Time (LMT) is the local hour angle of the Mean Sun measured westwards from the meridian of a certain place and expressed in terms of time instead of arc.

Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) is the local mean time anywhere on the meridian of Greenwich. In other words it is the Local Hour Angle of the Mean Sun on the meridian of Greenwich. Since the Greenwich meridian is used as the base meridian from which the longitude of all places on Earth are identified, it provides the link between the LMT of a place and the LMT at Greenwich (or GMT).

Standard Time. For each place on Earth to keep its own local mean time would obviously cause a great deal of confusion and difficulty. For this reason, Standard Time is introduced so that places in the same locality can keep the same time. The time chosen is usually based on a convenient meridian running through the area and the meridian chosen usually differs from the Greenwich meridian by a whole number of hours. Some large countries, such as the U.S.A. have several different standard times.

Zone Time (ZT). It would be impossible for a ship at sea to keep to the time of its longitude because (unless it is travelling due north or south) the longitude will be constantly changing. For this reason, the sea areas of the Earth are divided into time zones which are 15o of longitude (or 1 hour) apart. The central meridian of each zone is an exact number of hours distant from the Greenwich meridian so that zone time differs from GMT by multiples of 1 hour. The time kept in each zone is the time of its central meridian and is plus or minus GMT depending on the zone’s position east or west of Greenwich.

Time Zone System. The Earth is divided into 24 zones of 15o of longitude each, with the centre of the system being the Greenwich meridian. Therefore, the centre zone (zone 0) lies between 7.5o W. and 7.5o E. The zones lying to the West of Greenwich are numbered from +1 to +12 and those to the East from -1 to 12. The 12th zone is divided by the meridian 180o which is known as the International Date Line. The two halves of the 12th zone are marked + or – depending on which side of the date line they lie.

Time difference between meridians of longitude.

We know that the Earth revolves about its axis once every 24 hours. In other words, the Sun completes its apparent revolution of 360o in 24 hours. This means that the Sun crosses each of the 360 meridians of longitude once every 24 hours. So, in 1 hour, the Sun appears to move 15o,

in 4 minutes, it appears to move 1o,

in 1 minute it appears to move 15′,

in 4 seconds it appears to move 1′.

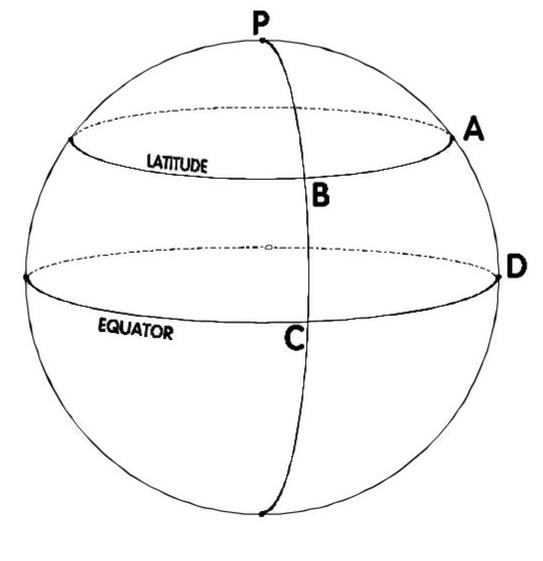

Declination. The Declination of a celestial body is its angular distance North or South of the Celestial Equator. The declinations of the stars change very slowly and can be considered to be almost constant for up to a month at a time. The declination of the Sun, on the other hand, changes relatively fast from 23.5o North to 23.5o South and back again during the course of a year.

Declination can be summarised as the celestial equivalent of Latitude since it is the angular distance of a celestial body North or South of the Celestial Equator.

The Equinoxes. The Sun crosses the celestial equator on two occasions during the course of a year and these occasions are known as the equinoxes. At the equinoxes, at all places on Earth, the nights and days are of equal duration (i.e. 12 hours) hence the term equinoxes (equal nights). Because the Sun is on the celestial equator at the equinoxes, its declination is of course 0o.

The Autumnal Equinox occurs on about the 22nd.September when the Sun crosses the celestial equator as it moves southwards from 23.5oN , the northernmost limit of its declination.

The Vernal Equinox occurs on about the 20th.March when the Sun crosses the celestial equator as it moves northwards from 23.5oS, the southernmost limit of its declination.

The Solstices. The times when the Sun reaches the limits of its path of declination are known as the solstices. The word solstice is taken from ‘solstitium’, the latin for ‘sun stands still’. This is because the apparent movement of the Sun seems to stop before it changes direction

The Summer Solstice (mid-summer in the northern hemisphere) occurs on about 21st. June when the Sun’s declination reaches 23.5o North (the tropic of Cancer).

The Winter Solstice (mid-winter in the northern hemisphere) occurs on about 21st. December when the Sun’s declination is 23.5oSouth (the tropic of Capricorn).

The Autumnal Equinox occurs on about the 22nd.September when the Sun crosses the celestial equator as it moves southwards from 23.5oN , the northernmost limit of its declination.

The Vernal Equinox occurs on about the 20th.March when the Sun crosses the celestial equator as it moves northwards from 23.5oS, the southernmost limit of its declination.

Note. The latitude of the tropic of Cancer is currently drifting south at approximately 0.5’’ per year while the latitude of the tropic of Capricorn is drifting north at the same rate.

Note. It has only been possible to give a brief explanation of this topic here. A fuller exposition is given in the book Astro Navigation Demystified.

Other links:

You must be logged in to post a comment.